Vienna – Berlin. The Art of Two Cities

As early as the late nineteenth century, both Berlin and Vienna were considered as rising metropolises. Nevertheless they have always, to the very present, represented divergent models of identification and different cultural self-concepts. Whereas the mutual exchange between the two cosmopolitan cities has already been intensively explored in terms of literature, theatre, and music, the juxtaposition of developments in the visual art and an analysis of their correlations constitute a blind spot. From an art historical perspective, they have merely been recognised in the form of individual biographic studies.

Spanning the period from the early twentieth century to the interwar years, Vienna – Berlin. The Art of Two Cities, organised in cooperation between the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere and the Berlinische Galerie, is the first exhibition to be devoted to artistic parallels, differences, and interactions between the two cities.

On the one hand, there is Berlin, a vast metropolis without a grown centre that almost gives an American impression; Vienna, on the other hand, the city of operettas, is determined by Baroque form and primarily associated with Decadence. Whereas Vienna was the capital of a venerable monarchy, Berlin was forced to establish itself as the new centre of power against pluralistic tendencies in the German Empire. Accordingly, the visual arts in Berlin evolved as a means of propaganda either promoting the Prussian pursuit of hegemony or in opposition to it.

It was different in Vienna, where the Habsburg monarchy allowed avant-gardist cultural ambitions, which were supported by the liberal bourgeoisie, to unfold. “Whereas the Berlin Secession, first of all, had to fight for artistic freedoms, the Vienna Secession could rely on the support of the upper classes, whose members largely financed the Vienna Secession’s magnificent building,” says Agnes Husslein-Arco, Director of the Belvedere.

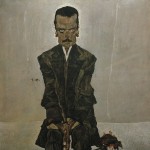

“The attitude of the Berlin avant-garde, oppositional throughout, is reflected by the fact that the Berlin Secession took a hostile stance towards the young Expressionists, while in Vienna Gustav Klimt promoted such young artists as Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele, and Max Oppenheimer like a father figure,” exhibition curator Alexander Klee points out.

The exhibition concept is based on the collections of the two collaborating museums and harks back to the idea with which the Modern Gallery, today’s Belvedere, was founded: the documentation of Austrian art, its international relations and connections. The relationships, similarities, and differences between the Secessionist movements of the two cities, launched shortly after each other, constitute the points of departure of Vienna – Berlin. The importance of the decorative arts and of form in general for the Vienna Secession is illustrated by the works of Josef Hoffmann, while works by Eugen Spiro and Max Liebermann demonstrate the orientation of the Berlin Secession on French Impressionism.

Towards the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, Expressionist movements began to emerge in both cities: whereas the Expressionists in Vienna stood out for their great psychological empathy, those in Berlin attracted attention because of their ecstatic and aggressive gestural style. The show highlights works by Max Pechstein and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who formed the New Secession in Berlin in opposition to the established Secessionist movement, and introduces such Expressionists as Ludwig Meidner, Conrad Felixmüller, and Rudolf Belling; on the other hand, it presents works by Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, Anton Faistauer, and Max Oppenheimer, who were supported by the group around Klimt in Vienna.

The First World War brought about a rapprochement between Austria and Germany, so that a lively artistic exchange evolved primarily in the field of stage design and with regard to the burgeoning movement of New Objectivity. Friedrich Kiesler, for example, whose Constructivist hanging system is integrated into the show, had first successes in Berlin and in 1924 organised an international show for theatre engineering in Vienna, which in turn brought numerous exponents of the Berlin avant-garde to Austria. At the same time, the movement of Viennese Kineticism, with its references to Expressionism and Futurism, gained influence: the show at the Lower Belvedere presents a number of works by Erika Giovanna Klien and others.

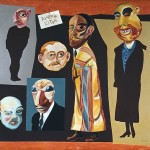

Kineticism in Vienna developed alongside the movement of Dada in Berlin, which dealt with social conditions in a critical and subversive manner, thereby creating what may be called an anti-culture.

Especially the Roaring Twenties, when opposite positions converged and the artistic exchange intensified, allow a new perspective of the connections between the two different capitals, which were nevertheless closely intertwined – social criticism and aestheticism, a Cubist language of form and verism increasingly overlapped. Herbert Boeckl, for example, could be encountered in Berlin, whereas the principal works of Christian Schad were created in Vienna.

The show also does justice to this development with works by Otto Dix, Rudolf Schlichter, George Grosz, Albert Paris Gütersloh, Anton Kolig, and Rudolf Wacker.

Moreover, the exhibition elucidates the importance of the competing art periodicals Aktion, Sturm, and MA. On view are works by Max Beckmann, Rudolf Belling, Herbert Boeckl, Conrad Felixmüller, Helene Funke, George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Josef Hoffmann, Johannes Itten, Friedrich Kiesler, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erika Giovanna Klien, Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, Lotte Laserstein, Max Liebermann, Jeanne Mammen, Ludwig Meidner, László Moholy-Nagy, Koloman Moser, Felix Nussbaum, Max Oppenheimer, Max Pechstein, Christian Schad, Egon Schiele, Arnold Schönberg, Franz Sedlacek, Renée Sintenis, Rudolf Wacker, and many others.

Vienna – Berlin. The Art of Two Cities has been organised in collaboration between the Belvedere and the Berlinische Galerie.