Rosângela Rennó

Rosângela Rennó – Strange Fruits

Fotomuseum Winterthur

09.06.-19.08.2012

The term Appropriation Art in the narrower sense is used when an artist deliberately copies individual works by other artists with a specific creative strategy in mind. This is a form of appropriation that is not considered plagiary but intentional artistic borrowing. The work of the Brazilian artist Rosângela Rennó clearly demonstrates elements of such appropriation. Her oeuvre consists largely of photographs, but these are almost never taken by the artist herself; instead Rennó finds them in private and public archives, at flea markets, through research, and over the course of her travels to dealers and markets throughout the world. Sometimes she integrates the found albums and photographs directly into her work, but more often she re-photographs the images, thereby altering their materiality, appearance, and size. For example, small 3 x 4 cm photographs or 8 x 10 inch glass plates are turned into 165 x 118 cm images.

Nevertheless, her work differs substantially from well-known forms of appropriation. Appropriation Art usually results from situations of abundance or even overabundance. However, Rennó’s artistic approach is very different, in fact, completely opposite: “In a country that remains unwaveringly devoted to the promise of progress (which is presumed to imply a rejection of the past), it is not without irony that photography, both a crucial agent of modernization and a witness to the crimes of modernization, would ultimately be trampled under the ceaseless thrust of modernity“ (Cuauhtémoc Medina). Brazilian society seems to be pressing forward with devouring strength, systematically pushing aside and forgetting the order of what has gone before, the memory of the past; certain memories are obliterated either through neglect or by design. Everything that hinders advancement, progress, or the future is unrelentingly swept below the surface. Socio-cultural memory is ideologically filtered.

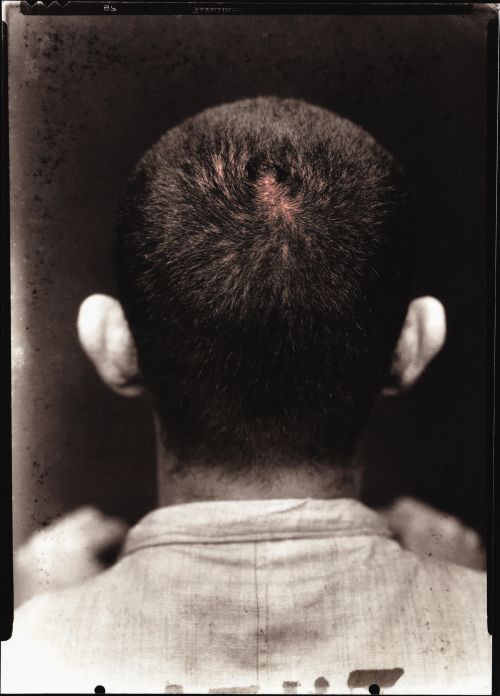

The use of appropriation to counter the loss of memory is a driving force in the work of Rosângela Rennó. It is a form of fighting collective repression and a future that is void of a past; appropriation is a means of combating emptiness, the vacuum in the kickback of the motor of the future. In her own way Rennó seems to operate as a tracker. This is true of her early work Imemorial, in which she updates portraits of workers who died during the construction of the future-oriented city of Brasilia. In this piece she develops her first visual work of mourning, which counteracts the intended or unintended obliviation of the victims of a major national project, the burying of the past in the service of the future. In the works Cicatriz (Scar) and Vulgo [Alias] Rennó performs a kind of mental archaeology, in which photographs of former inmates, glass plate images she discovered in the Carandiru jail in São Paulo, are enlarged to an almost painful dimension, so that in looking at the over-sized images we physically sense the coldness of these early formal identity photographs, on the one hand, and the living presence of the individuals (including all their scars, tattoos, imperfections of the skin and stubborn whorls of hair), on the other. The work serves as a visual embodiment of what has been pushed into the subconscious, the belated but significant emergence of the prisoners from anonymity.

All of Rennó’s works to date, including her video works, address mental states of the present; they interrogate how the past is dealt with and how knowledge from the past is integrated into the present and the future. They bear witness to the ideological underpinnings of the controlled loss of cultural material. By uncovering a forgotten legacy of images they reveal rampant cultural amnesia. Her works can be read as a repositioning of Appropriation Art in a political and cultural context. Tending towards the three-dimensional, the sculptural, and installation, the works suggests Rennó’s desire to show this amnesia in the most physical manner possible, allowing what has disappeared to manifest itself again as “flesh” to the greatest extent possible. Her found objects do not always have an immediately obvious cultural significance; sometimes they are “merely” Strange Fruits (Frutos estranhos). But they always take the form of politically aware cultural archaeology, inspired by the determined attempt to establish a visual anthropology of Latin America.