Into India

Into India – South Asian Paintings from the San Diego Museum of Art

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

28 February – 20 May 2012

From 28 February, the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza will be holding the first exhibition in Spain of a selection of South Asian paintings from the San Diego Museum of Art, California. The exhibition will offer visitors a unique opportunity to appreciate the entire evolution of Indian painting from the 12th to the mid-19th centuries through 106 paintings, prints and manuscripts. Together they reveal the remarkable capacity of the artists who created them to adapt and modify their traditional styles without losing their uniquely Indian character.

Assembled by Edwin Binney (1925-1986) and comprising nearly 1,500 works, this exceptional collection is defined by its encyclopaedic, academic nature, as a result of which it offers a comprehensive survey of the history of Indian art. Binney’s aim was to ensure that every expert in South Asian artist found a key work in relation to their particular subject of research in his collection. According to Professor Pramod Chandra of Harvard University, one of the first experts on Indian art: “The collection includes numerous works of outstanding quality, both in themselves and for the way that they cast light in an exceptional manner on the nature of a style. I know of no other collection assembled by a single person that has achieved that aim, which is so difficult and requires so much thought.”

Indian painting varies considerably from region to region and also depends on period and class structure, although it also reveals shared characteristics that survive across time and geography, including the above-mentioned flexibility of the artists in question and in particular their minutely detailed, painstaking approach. The use of extremely fine

brushes, sometimes made with just two hairs, and of magnifying glasses allowed artists to paint these works, which are almost miniatures, encouraging the viewer to study them at length in order to appreciate the wealth of details in the depiction of figures, backgrounds and landscapes. Long years of such painstaking work meant that many artists went blind at an early age and had to abandon their craft. In addition, continuous exposure to the toxic substances of which the pigments were made, including arsenic, lead and mercury, ultimately affected their health.

Painters’ workshops were organised according to the different levels of specialisation and skill of those working in them. For example, in workshops that specialised in manuscript illumination the master would first sketch out the composition, then the young painters would apply the initial layers of colour, after which the specialists would add the faces, trees and other motifs. Lastly, the work would be returned to the master for the final touches. Once complete it would be burnished with a piece of agate in order to compress the layers of pigment and add a distinctive shine that is one of the most characteristic qualities of Indian painting.

The activities of these artists, who followed their family’s trade or caste tradition, tended to be anonymous. In some cases, however, principally under the patronage of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (16th century) and his successors, a few painters became known individually and their work came to be highly appreciated by collectors.

The exhibition is organised into four thematic sections that also follow a chronological order, starting in the 12 th century with some early examples of manuscript tradition in the autochthonous style, and concluding in the 19th century with the transferral of Mughal imperial power to the Raj, the British system of colonial rule.

Sacred Illuminations

The exhibition opens with a gallery of works that illustrate sacred texts given as offerings to temples. Commissioning copies of these texts was a religious act that increased karma: a concept based on the belief that all action (karma in Sanskrit) has its consequences.

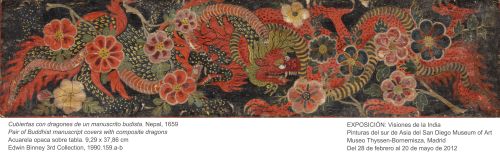

The tradition of illuminating manuscripts began to flourish in India around the 11th century in Buddhist monasteries with the production of scenes that embellished copies of the sacred texts and acted as aids to meditation. Indian painters used this repetitive, traditional style with its limited range of colours and themes until the 15th century when the dissemination of illustrations produced in court workshops and the training that local artists received in them enriched and revived sacred illumination. Artists began to illustrate new texts, including the victories of the goddess Kali, devotional works dedicated to the god Krishna and philosophical texts. This section includes outstanding examples of all these types.

Lyric Visions

This section focuses on the paintings that illustrated the most popular Persian literary narratives from the 15th century onwards. They were commissioned by elite clients who were no longer interested in increasing their spiritual merit but in encouraging the production of these works as a sign of education, wealth and cultural sophistication. One of the first literary texts to be illustrated in India was a version of the Khamsa [Quintet], a group of five Persian poems written in the 13th century that recount the conquests of Alexander the Great and the amorous and epic deeds of various historical characters. The minute detail and sumptuousness of these illustrations can be seen in the examples on display in this section, which include two pages from the Khamsa in a 15th-century version.

Unfolding the History of Mughal Painting

Imperial Mughal painting is one of the most influential and esteemed types of Indian art. The Emperor Akbar (1556-1605) was partly responsible for this artistic flowering when he summoned around a hundred artists to work for him in

the imperial workshop under the direction of seven painters from the Persian court. Adhering to the realism that was the Emperor’s preferred mode, these collaborative works by Indian and Persian artists together form an outstanding group executed in a new style and characterised by an unprecedented vitality. Both Akbar and his successors were interested in the European prints that began to arrive in India in the 16th century with the Jesuit missionaries. These prints inspired Indian artists in the same way that the arrival of Mughal painting in 18th-century Europe encouraged western painters to include near-eastern motifs in their works. This inter-cultural dialogue, which manifested itself in the form of aesthetic borrowings and in the rise of stereotypes of the exotic, constitutes an important chapter in the story of the external influences that helped to configure Indian painting.

In the Company Manner

The works executed by Indian artists for British civil servants and merchants associated with the East India Company reflect Indian artists’ interest in the scientific methods that had become widespread in 18th-century Europe and the resulting realism with which they represented the local flora and fauna. Such images reveal how Indian artists interpreted European artistic conventions: shading, perspective, muted colours and a certain sense of distance between the viewer and the work. Works of this type, produced under British rule, continued the Mughal interest in the depiction of animals, as well as the technical skill, vibrant colouring and compositional mastery characteristic of the earlier period.

Demand for images of this kind diminished after 1848 when the Company began to make use of the new medium of photography, which largely replaced painting as a means of documenting the people and places of India under British rule.